Dangers Of Separating Children From Caregivers: A Podcast With Darcia Narvaez

What are the dangers of separating children from their caregivers? How does this early trauma impact lifelong wellness, or illness, for all homo sapiens?

Visit Kindred’s sister nonprofit initiative, The Evolved Nest, at www.EvolvedNest.org.

Dangers of Separating Children from Caregivers: TRANSCRIPT

Mary Tarsha: Hello, thank you again for joining us. I’m Mary Tarsha. I have here Dr. Darcia Narvaez. Thank you, Dr. Narvaez, for being here with us today.

Dr. Narvaez: You’re welcome.

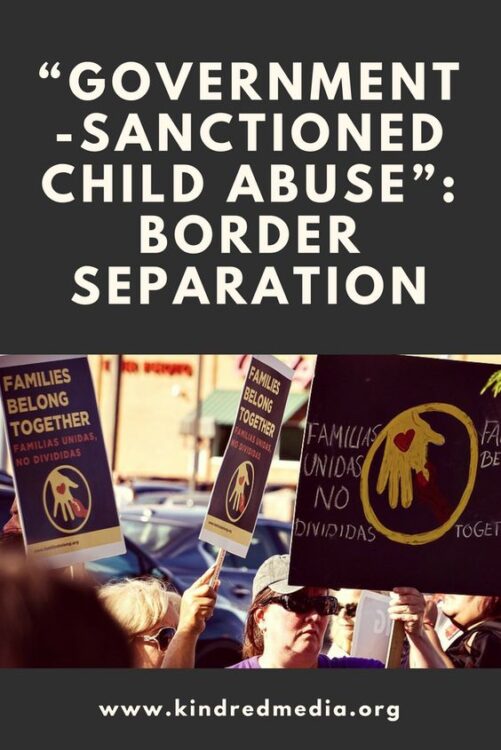

Mary Tarsha: Today we’re talking about something that has been present in our era now for several months. I’m talking about the issue on the border of separating children from their parents, as we see prospective immigrants are being separated from their children. We’re talking about the psychological effects of what happens when you separate children from their caregivers. So, thank you, Dr. Narvaez. How would you begin talking about this very relevant issue for today?

Dr. Narvaez: Sure, I’m happy to talk about this. It is really a critical issue for today’s world. Let me just say that the primary caregiver isn’t necessarily a parent but could be a grandparent or an aunt, uncle or even a friend. So what I’ll talk about is primary caregivers rather than a parent in my discussion.

First, I think we have to step back a little bit and understand what human beings are, who we are, what we need to grow and flourish. We’re animals– we need nourishment and warmth and so that means food, we need to be kept warm and in shelters, but that’s hardly enough to grow well, it’s just to keep you alive. We’re also mammals and mammals need lots of affection, lots of touch positive touch and play, playing with others in self-directed ways. But we’re also social mammals which means we need bonding with the community, not only with our primary caregiver but also with others who make us feel like we belong, like are accepted, loved and appreciated.

MT: Interesting. Yes, so these are all things that are important in order just to not only survive but to develop well and to flourish. It applies here because before we can begin talking about the effects of being separated as a child from a caregiver, we need to be talking about infants and children need, what humans need.

DN: If we zero in on early childhood, that’s zero to six essentially. That’s when a child is constructed or co-constructed by experience in the caregiving environment. Our biology is constructed by our social environment. Then later, as we express our social capacities, they are reflective of how well our biology was constructed in the early years.

MT: That is so profound. That is just a jam-packed statement–that we are biosocially constructed. So we don’t develop in a vacuum but experience really influences our biology for years to come.

DN: That’s right. So we have to pay attention to those early days, months, years of a child’s life because they are actually putting the child on their trajectory towards better or worse health. When you undermine early experience for the things I’m going to talk about, then you’re kind of undermining who the child’s going to be for the rest of their life. They might have problems with their immune system or with depression or anxiety because they had the rug pulled out from under them in early childhood.

MT: That’s interesting.

DN: So when we talk about what is it that humans really need, we must understand that we have a nest like all animals. We have a nest that evolved to optimize normal development. We call that a developmental system. If you provide this developmental system, you’re going to have a very good outcome; you will have a normal outcome for that species and you’ll have a smart and effective creature.

Let me go through the nest for young children. We study this in my lab because it’s so vital for how that life course is going to go for that child for the rest of their lives.

MT: And you’ve said before that we’re talking about the things that are most critical in order to develop properly and have a child flourish. But these things are provisioned by the community so that means that it’s provided by everyone involved. It’s not just putting more emphasis on what mom or dad or that one primary caretaker should do, right?

DN: That’s right. So the evolved nest involves multiple components:

(1) having a soothing perinatal experience. That means mom is supported and feels relaxed during pregnancy because if she doesn’t there’s all sorts of things that can misdirect development. It also means that she and baby have a soothing birth experience, not one that’s stressful, like separating baby from mother or introduces painful procedures and things like that.

(2) Another one is touch. We need touch to grow well. That’s affectionate touch, not punishment, not corporal punishment, which actually misdirects development in various ways.

(3) Responsiveness means meeting the needs of the young child, the baby, promptly, before they get upset and distressed. It means following their signals of their face, or voice, or their wiggling before they start crying.

(4) Then there is breastfeeding. We are called mammals because of mammary glands. Mothers provide species-typical milk which for us is a thin variety of milk. This means it should be ingested frequently also because it’s full of hormones and all the building blocks of the brain and body. As babies, we expect to be nursed frequently two or three times an hour initially–when we’re very young, our stomachs are so tiny. Our species expects to be breast fed for two to five years on average, according to the studies around the world looking are small-band hunter gatherers, the kind of societies that represents 99% of human history.

(5) Alloparents or allomothers. It’s not just mom, as you’ve mentioned already, that cares for the baby but other adults fathers, grandmothers in particular that are also providing the touch and responsiveness and the soothing kind of experience that babies need to grow well

(6) And then there is play. Social, self-directed free play in the natural world with lots of different aged playmates which also grows the individual’s brain and body well.

All these characteristics are neuroscientifically shown to matter for mammal development.

(7) And finally, social support–feeling highly socially embedded in the community, having a sense of belonging, a sense of being appreciated, where you can be yourself.

So let me just mention them quickly again: soothing perinatal experiences, positive touch and affection, responsiveness, breastfeeding, allomothers or alloparents, social free play, and social support.

MT: That can seem overwhelming when you hear all of them together but when you are reminded that this is a community that is coming together that is caring for the needs of this child then it becomes much more understandable. It’s an experience where the needs of the child are being met from many people surrounding the child so then they grow up feeling, as you said, very deeply embedded within society and connected and their needs are very satiated going forward.

DN: When their basic needs are met, then their body and brain develop well.

All these factors are related to self-regulatory systems that come on line, that are their setting parameters, how they are going to function, during early sensitive periods.

Let’s just talk about one: touch. When you separate a mom and a baby or a caregiver and a child ,that child’s not going to get the touch they need. When you separate a mammal baby in particular, but also children, it’s going to dysregulate multiple systems, causing lifelong changes in stress responsiveness, causing deficits that will contribute to violent and antisocial behavior and also to depression, even later in life.

MT: It’s really interesting because when we’re talking about separating child from the caregiver, this is immediately just a no brainer right of what they’re going to be deprived of—physical closeness and affectionate touch. The literature is converging on this. We see this over and over again and different studies, both human studies and animal studies, that when you’re depriving physical touch it’s really having an effect neurobiologically for years to come.

DN: Yes, and we know that when you’re separated from your mother, baby’s pain responses increase, and endogenous opioids—those things that make you feel good that are internal to your body and that actually are fostered by touch and being with your parents—those things diminish. Your oxytocin, which is the so-called cuddle hormone, decreases and so on. If these things happen during a sensitive period, it can have lasting epigenetic effects on that child. For example, we know if in the first six months you need lots of touch, affectionate touch, for turning on the controls of anxiety. If you don’t get enough touch at the right times in the right way, you’re likely to have an anxious personality for the rest of your life, unless you take drugs and medicate your anxiety. You will find the ways to medicate yourself with drugs, alcohol, addictions.

MT: It all goes back to physical closeness and affectionate touch.

DN: And we know that close physical positive touch affects your stress response, your immune system, your endocrine systems, such as the oxytocin system, neurotransmitters—how many you have and how well they function. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that’s linked to intelligence but also to wellbeing. Emotion systems and various other things are affected that can be undermined if you are separated or don’t have enough touch.

The child who is not provided with the evolved nest feels very deep down that something is not right. The feeling of what the child should have a sense of was well described by Jean Liedloff in The Continuum Concept, a book she wrote after she was sort of an accidental anthropologist, and tried to contrast what was going on– why are these kids and adults here in this Amazon jungle so happy and so well, and I go home to the States and, boy, everyone is so unhappy and sick:

“The feeling appropriate to an infant in arms is his feeling of rightness, or essential goodness, the premise that he is right, good, and welcome. Without that conviction, the human being of any age is crippled by a lack of confidence, of full sense of self, of spontaneity, of grace.”

MT: Oh my goodness, what a quote It is really beautiful.

DN: So when we undermine nest provision, all those characteristics that I mentioned and we’re focusing here on touch, that child’s sense of confidence and wellbeing in the world is undermined. She talked about that babies were meant to fall asleep in arms, in someone’s arms, to be carried around all day long, sleeping, awake whatever it is and that gives you this sense, of rightness.

MT: Even in that quote you see the full sense of self confidence, spontaneity, of grace. Very profound. You can just see that when a child is being held and cuddled in that right, ordered relationship, responsive parenting, that it provides a foundation for the rest of his life.

DN: Sensitive, responsive care in general provides a sense of well-functioning psyche and physiology. So what do we mean by responsive care? It is that synchrony between you and the child, the adult and the child, where you’re able to communicate back and forth and understand each other’s nonverbal communication, to coordinate to get along well, and have a sense of being connected with an external umbilical cord. You co-regulate one another. That’s we mean by responsive care

MT: Almost like a dance, right?

DN: Yes, an interpersonal dance is a nice way to say it. So, both of these, responsiveness and positive touch, are affecting various physiological systems, including how well the vagus nerve works. It’s the 10th cranial nerve that’s connected to all the major systems of the body: cardiac system, respiratory, immune system, emotional systems, digestive systems. And these are critical connections because they are established in early life. If you don’t have the responsive and affectionate care, the vagus nerve can be mis- or under-developed and then any one of these systems can be dysregulated as a result.

MT: I think you might talk about this later but also the social engagement system–how the vagus nerve is very much part of that social engagement system. When you are undercared for in early life and you develop a compromised vagus nerve, the 10th cranial nerve, then that really hinders you for the rest of your life going forward in how you engage with others, in the ease with which you engage with others.

DN: Right. Vagal tone, which is what we call it when the vagus nerve is functioning well, if you have a good vagal tone it allows you to be intimate with others because you’re able to calm yourself down to keep the sympathetic system from taking over, or the parasympathetic system, and instead the social engagement capacities are there. And so you can respond to others in intimate ways, but also with compassion if they’re in distress or need.

One of the critical things that’s happening in these early years is the right hemisphere development, zero to three in particular. Many things are right lateralized in those early years so the vagus nerve, for example, is related to self regulation, self control, and there’s so many systems that are involved in this– we kind of talk at the very general level here. But they all contribute to your ability to be who you are, as your unique self, being guided by your intuition, well developed intuitions and emotions, being able to be empathic towards others, to be present in the moment, to be receptively intelligent, so you can pick up signals from others. All these things are governed, initially at least, by the right hemisphere and that needs to develop well in the early years.

MT: Yes, and what you’re saying is that the right hemisphere is dominant in the early years, meaning that there’s more development in the right side of the brain that is taking place, but is controlling all of these very important aspects of empathy, beingness and receptive intelligence and higher conscious compared to the left side which will then develop later on in life.

DN: Right, throughout childhood it is the right hemisphere that should be dominating. That’s the time period for it to be developing from experience, from whole body experience. Left hemisphere is more of that conscious mind that we educate in school. That’s fine for adolescents, but before then, as much as possible, you want to have your child immersed in whole body experience.

So what happens if you’re undermining development in early life from undercare? Your survival systems that you’re born with, which are integrated with the stress response, take over, easily, your mind, and control how your whole brain functions. That kind of wipes out your ability to think very well, think very openly, think very good heartedly, and those things can then undermine who you are. You are almost conditioned to be stress reactive and then go into this fight-flight-fight-freeze-faint or anger, fear or panic easily.

MT: They are very activated. Under care is provided, or in this situation, separation from the caregiver ,then you’re going to have an increase in the stress response and an undermining of right hemisphere development leading to this exaggerated exponentiated fight-flight-freeze-faint.

DN: That’s right and so then you will have a personality that’s more oriented to being socially oppositional, distrustful of others, or just withdrawn in fear and passivity, and kind of shut down too. In both cases you’re trying to feel safe and because your brain did not develop properly you only know this way of functioning, either dominating and opposing, and you know, standing on the hill over others, or withdrawing and hiding out of fear.

So when you separate a child from a parent or caregiver you are, in effect, encouraging this kind of personality to develop. And you can see this fight or social opposition in terrorists who have been traumatized in their own childhoods and then grow up to take on perspective of the world that they’re going to ‘defeat those people who hurt them.’

MT: The enemy, the enemy.

DN: Right, whomever you are told the enemy is. That will vary by culture and by what kind of environment you put yourself into. But you will take up an enemy. And you will want to defeat that enemy and you’ll be always oriented to enemies and crises. This is not our heritage as human beings. Our heritage is to be cooperative with others, to be open and hospitable to others, wherever they’re from.

MT: Right, so then we see as you’re talking about both of these different reactions being having behavior that’s socially oppositional or socially withdrawn, that basically these are two outcomes or two types of behavior that that stem kind of from a similar trajectory, a similar developmental path with under care.

DN: That’s right. And so I think we have to be cautious now when we think about separating children from parents no matter where they are, if they’re going to jail, if they’re at the border, wherever you are in the society, whatever level within any community: if you separate the child from the parent, expect trauma. And we should avoid trauma.

MT: Even with high social economic status.

DN: Yes, no matter who you are. Young children especially, but throughout childhood. We need to be with our caregivers. We need lots of affection. We need responsiveness. Putting kids into jail or camps or tents by themselves, without their caregivers is highly traumatic.

MT: Highly traumatic, right.

Thank you so much Dr. Narvaez. It is really helpful to have you explain to us the effects of separating a child from the caregiver. Thank you again for joining us and we look forward to being with you next time.

About the Evolved Nest

Every animal has a nest for its young that matches up with the maturational schedule of the offspring (Gottlieb, 1997). Humans too! The Evolved Nest (or Evolved Developmental Niche; EDN) refers to the nest for young children that humans inherit from their ancestors. It’s one of our adaptations, meaning that it helped our ancestors survive. Most characteristics of the evolved nest emerged with social mammals more than 30 million years ago.

Humans are distinctive in that babies are born highly immature (only 25% of adult-sized brain at full-term birth) and should be in the womb another 18 months to even resemble newborns of other species! As a result, the brain/body of a child is highly influenced by early life experience.

Multiple epigenetic effects occur in the first months and years based on the timing and type of early experience. Humanity’s evolved nest was first identified by Melvin Konner (2005) as the “hunter-gatherer childhood model” and includes breastfeeding 2-5 years, nearly constant touch, responsiveness to baby’s needs, multiple responsive adult caregivers, free play with multiple-aged playmates, positive social support for mom and baby.

Calling these components the Evolved Nest or Evolved Developmental Niche, Narvaez and colleagues add to the list soothing perinatal experience (before, during, after birth) and a positive, welcoming social climate. All these are characteristic of the type of environment in which the human genus lived for 99% of its existence. Below are publications and a powerpoint about the evolved nest.

Why does the evolved nest matter? Early years are when virtually all neurobiological systems are completing their development. They form the foundation for the rest of life, including getting along with others, sociality and morality.