Which America? Which Christianity? Which Path?

John Lewis trudged towards justice and invites us along.

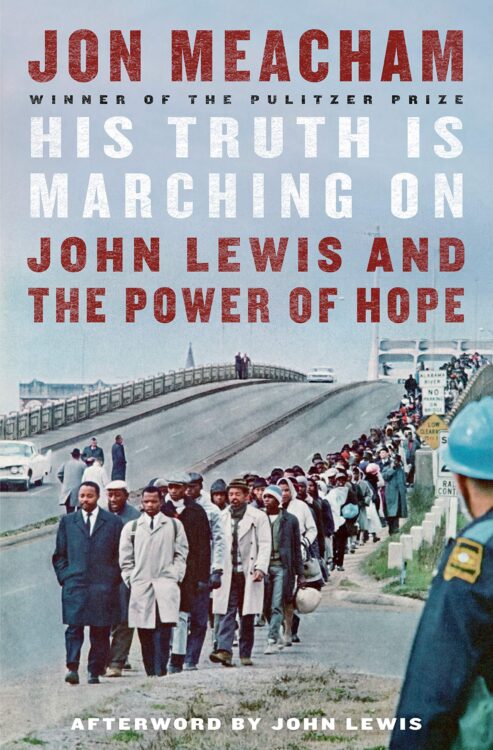

Jon Meacham, Pulitzer prize-winning historian, published a book shortly after Congressman John Lewis passed away in July 2020, His Truth is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope. In the book, Meacham focuses on Lewis’ first 28 years or so, showing how he learned his craft for “good trouble.”

Meacham’s book attempts to demonstrate how John Lewis “was as important to the founding of a modern and multiethnic twentieth- and twenty-first-century America” as the founding fathers were in creating the republic in the eighteenth century. “This is not hyperbole. It is fact—observable, discernible, and undeniable fact.” (Meacham, 2020, p. 5)

The Beginnings

Lewis was born to sharecroppers in a segregated and poorly served community in Alabama. Beyond the daily humiliations of hand-me-down schoolbooks and decrepit buses, rusty spigots as drinking fountains for “coloreds,” was the constant threat of violence. Meacham describes the crimes against innocent Blacks in Lewis’ childhood (gang rapes, mob murders of those who did not act in the right manner around a white person, murders of civil rights activists). Lewis remembered: “From my earliest memories, I was fundamentally disturbed by the unbridled meanness of the world around me…I could feel in my bones that segregation was wrong, and I felt I had an obligation to change it” (Lewis, 2012, p. 95).

From early childhood Lewis had wanted to be a preacher and, famously, practiced giving sermons to the farm’s chickens. The preacher in his home church focused on the hereafter, with little to say about this life, the life between the cradle and grave. Lewis interpreted the Gospel differently. He thought that God was concerned with how people lived their lives here and now, that everything a person did had to be more than just an interim before reaching heaven.

At age 17, Lewis went to Nashville’s American Baptist Theological, a preaching school. There he was inspired by integration efforts by other activists and decided he wanted to try to integrate Troy State. He wrote Martin Luther King Jr. to get advice. King traveled to meet him to find out who this young man was and whether he had the strength to do such a thing. He did, but when he approached his parents, the possibility of physical and economic danger to the large extended family was too much a concern. So Lewis gave up the idea and stayed in Nashville at ABT. He searched for another opportunity and found Reverend James Lawson.

The Practice of Nonviolence

Lawson, from his experiences in prison as a conscientious objector during the Korean War and time spent time with Mahatma Gandhi, wove “the threads of faith, philosophy, and justice together into a larger tapestry” of action (Meacham, 2020, p. 57). Lawson held weekly workshops on nonviolent action that gave Lewis the tools to move his dream forward.

Nonviolence was a way to love the other. In an interview for the documentary, The Soul of America, Lewis recalled:

“We studied the whole idea of passive resistance. We studied the way to love. That if someone beat you, or spit on you, or poured hot water or hot coffee on you, you looked straight ahead and never ever dreamed of hitting that person back or being violent toward that person … Hate is too heavy a burden to bear. If you start hating people you have to decide who you are going to hate tomorrow, who are you going to hate next week? Just love everybody.”

It wasn’t enough to resist one’s urge to strike back at an assailant, one must not even desire to hit back but instead love the person hitting you. (This is reminiscent of what Tibetan monks did while they were being tortured. See Salzberg, 1995.)

His first nonviolent demonstration was in solidarity with students in Greensboro, North Carolina who had been refused service at a segregated lunch counter. Hundreds of students sat at the segregated lunch counters in Nashville. Lewis was beaten and arrested with fellow students who sang “We Shall Overcome” on their way to jail. His most famous nonviolent action, at age 25, was on the march from Selma to Montgomery. He ended up with a cracked skull and a severe concussion.

Nonviolence is a radical worldview.

“Like the Sermon on the Mount, like the Passion of Jesus, nonviolence challenged power force, and self. The Nietzschean will to power has claimed far more adherents than the biblical admonition, first found in Leviticus, to love one’s neighbor as oneself. The past—and the present—is in many ways the story of how we have hated those neighbors and have loved ourselves and our own kind with decisive ferocity. Yet Lawson’s message to Lewis, and in turn Lewis’ message to America in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, turned history on its head. Love, not power, should have pride of place; generosity, not greed; kindness, not cruelty. Nonviolence … was not only a tactic. It was an enveloping philosophy, a compelling cosmology, a transforming reality.” (Meacham, 2020, p. 62)

For Lewis, Lawson and King, the aim was not just a more perfect union but a wholly new order, the Beloved Community. Lewis described it:

“‘Beloved’ meaning not hateful, not violent, not uncaring, not unkind, and ‘community’ meaning not separated, not polarized, not locked in struggle; the Beloved Community is an all-inclusive world society based on simple justice, the values, the dignity, and the worth of every human being, and that is the Kingdom of God.”

Inspiration

Lewis rejected the tragedy of life and history, dismissed the suffocating limits of pragmatism, and instead embraced the possibilities of realizing a joyful ideal.” (Meacham, 2020, p. 8). Lewis says that he was inspired by a number of books and scholars, including Horace Mann, the nineteenth-century educator who said: “be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity” (Treichler, 2011, p. 123).

Lewis was mobilized by the worlds of Martin Luther King Jr., who wrote:

“The gospel at its best deals with the whole man, not only his soul but his body, not only his spiritual well-being, but his material wellbeing. Any religion that professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about the slums that damn them, the economic conditions that strangle them, is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial” (King, 2003, pp. 37-38).

Before his death, John Lewis had written the afterword to Meacham’s book. He called Americans to hope and action.

“Fear is abroad in the land, and we must gather the forces of hope and march once more.” (Meacham, 2020, p. 248)

“As Martin Luther King Jr. taught us, whenever and wherever we see injustice, we had a moral obligation to say something, to do something, to speak up and speak out.” (Meacham, 2020, p. 247)

Lots of people make history. But Meacham points out:

“The question for Americans is what kind of history we want people to make … Individual decisions, individual dispositions of heart and of mind, matter enormously, even if change often feels out of reach.” (Meacham, 2020, p. 244)

John Lewis provides the path and example for change that is inclusive and caring. You can read his essay to the nation that he asked to be printed after his death.

Watch The Soul of America Trailer:

References

King, M.L., Jr. (2003). A testament of hope: The essential writings and speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. (J.M. Washing ton, ed.). San Francisco: HarperOne.

Lewis, J. with Jones, B. (2012). Across that bridge: Life lessons and a vision for change. New York: Hyperion.

Meacham, J. (2020). His truth is marching on: John Lewis and the power of hope. New York: Random House.

Salzberg, S. (1995). Loving-Kindness: The Revolutionary art of happiness. Boston: Shambhala.

Treichler, P.A. (2011). Metaphor and institutional crisis: The near-death experience of Antioch College. In B. Zelizer (Ed.), Making the university matter. New York: Routledge.